Δεκ 26, 2021 | Research

This country report has been prepared in the framework of the project ‘Social partners together for digital transformation of the world of work. New dimensions of social dialogue deriving from the Autonomous Framework Agreement on Digitalisation’ (TransFormWork VS/2021/0014).

Table of Contents

1. Historical Trends and Development of Digital transformation in partner country. 2

1.1. The structure of economy in Estonia. 2

1.2. Recent developments. 3

1.3. Forecasts and the future developments. 4

2. National framework of digitalization and collective bargaining. 8

3. The role or social partners. 10

3.1. State of play on the main issues, arranged by the FAA on Digitalisation. 10

3.2. Challenges and opportunities faced by social dialogue deriving from the digital transformation of the world of work. 11

3.3. Examples of good practice. 12

1. Historical trends and the development of digital transformation in the partner country

- What is the national structure of the economy?

- Development of digital transformation in recent years

- What are the forecasts for the future?

1.1. The structure of the economy in Estonia[1]

Estonia is a small, advanced economy, mostly influenced by EU and Scandinavian trade partners. GDP was EUR 27 billion in 2020, and will reach EUR 30 billion in 2021, which is around EUR 22,600 per capita. Estonia has only 1.3 million inhabitants, and the exporting of goods and services accounted for around 70% of GDP in 2020.

Estonia had the second highest activity rate in the EU in 2019 among the population aged 20-64, with unemployment being less than 5%, despite the work ability reform in 2018 that made an assessment of ability to work by the Unemployment Insurance Fund mandatory in order to receive support for reduced work ability. Active labour market measures are focused on career advice, upskilling and reskilling. A major emphasis is placed on language and basic IT skills.

Structure of enterprise. There are 137,000 companies in Estonia. Only about 40,000 of them have more than 1 employee, and only 7000 have 10 or more employees. In Q1 2021, the 5% of companies with 10 or more employees paid 75% of taxes and employed around 65% of the work force.

There has been a strong focus on ICT in Estonia since the restoration of independence. The impact of digitalisation has been stronger in public services and lags a bit in the private sector, especially in SMEs.

Some facts about digitalisation:

- High-technology and the knowledge-based service sector account for 4.8% of employment, which is 6th highest in the EU.

- ICT sector value added was 5.4% of GDP in 2018, which was 5th highest in the EU.

- ICT specialists accounted for 4.3% of total employment in 2018, which was 3rd highest in the EU. The share of all ICT sector employees reached 7.1% of the labour force in Q1 2021.

- A total of 62% of the population has basic or above basic ICT skills, which matches the average EU level.

- Digitalisation:

- Only 26% of Estonian enterprises use an ERP system in communication between different departments and business lines, whereas the EU average in businesses is 36%.

- A total of 80% of individuals have used the Internet in past 12 months for communicating with public authorities.

- There are 31 start-ups per 100,000 inhabitants (3rd in the EU).

Overall, the manufacturing industry accounts for the largest part of the economy. The manufacturing industry employs 18% of the labour force and accounts for 14–15% of GDP (see Table 1). Labour productivity in manufacturing is lower than the European average and the issue is being tackled largely through innovation and digitalisation. According to a survey conducted by Enterprise Estonia in 2020, 64% of industrial enterprises surveyed had computer-controlled machines, while 36% did not[2]. A third of the respondents said that their company collects and analyses data. Sensor technology was used by 22% of the companies surveyed. Drones are used by 15% of the industrial enterprises surveyed. Digitalisation and automation of production processes is more prevalent in large companies.

The second largest sector, retail and wholesale trade, accounts for 13.5% of value added and 13% of the labour force. Today, most retailers have launched their own online shops and have adopted self-service checkouts. Information flows are largely digitised and integrated (ERP systems, etc.).

The ICT sector itself accounts for 8.6% of GDP and nearly 5% of the labour force. The greatest challenge for the sector is finding new people to recruit. For this reason, ICT companies often expand to other Eastern European countries and elsewhere.

Table 1. Economic structure by industrial breakdowns of GDP and employment (Eurostat 2020)

| *** |

% of GDP |

% of employment |

| Activity sector: |

Estonia |

EU[3] |

Estonia |

EU |

| Total – all NACE activities |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

| Agriculture, forestry and fishing |

2.2 |

1.9 |

2.9 |

4.5 |

| Industry (except construction) |

18.6 |

19.4 |

20.1 |

16 |

| Manufacturing |

14.4 |

16.2 |

18.2 |

14.4 |

| Construction |

6.4 |

5.7 |

8.0 |

6.5 |

| Wholesale and retail trade, transport, accommodation and food service activities |

20.7 |

17.8 |

23.3 |

24.1 |

| Information and communication |

8.6 |

5.4 |

4.8 |

3 |

| Financial and insurance activities |

4.9 |

4.6 |

1.8 |

2.3 |

| Real estate activities |

9.2 |

11.4 |

1.7 |

1 |

| Professional, scientific and technical activities; administrative and support service activities |

9.5 |

11.1 |

8.5 |

12.5 |

| Public administration, defence, education, human health and social work activities |

17.3 |

19.8 |

23.2 |

24 |

| Arts, entertainment and recreation, etc. |

2.5 |

3.0 |

5.7 |

6 |

1.2. Recent developments

The COVID-19 pandemic has had an impact on economies and lives around the world. Fortunately, the negative impact on the economy is not as uniform as in the financial crisis of 2008-2010. As in many other countries, the ICT sector has actually seen strong growth during the pandemic. Exports of digital services have experienced strong growth in recent years, accounting for around 12-13% of total exports in 2020. The share of people employed in the ICT sector has increased from 4.8% in 2015 to 7.1% in the first quarter of 2021[4].

In addition, digital technology also suddenly became even more important for people working in other sectors. Nearly 200,000 employees, or about a third of the labour force, transferred to telework in Estonia in the second quarter of 2020, while the usual level is approximately 7%[5]. Nearly 90% of employees would like to see a permanent increase in the share of telework[6].

Data from the Labour Force Survey[7], collected during the emergency situation, shows that professionals (67.9%) and managers (57.2%) made the most use of teleworking, while the use was significantly lower among mid-level specialists (41.5%) and office workers (25.8%).

In a comparison of activities, teleworking was used the most by those working in information and communication (82.4%), finance and insurance (75.5%) and professional, scientific and technical fields (68.7%)[8].

The biggest increase in the share of people working remotely was in education: 19.5% in the previous year compared to 56% during the first wave of the coronavirus[9].

1.3. Forecasts and future developments

Estonia’s economy is projected to recover rapidly in 2022 and beyond (see Table 2), with unemployment expected to fall. Previous structural problems, such as a significant labour shortage, ageing society and inadequate funding for social services, will once again become more prominent than the health crisis.

Table 2. The general economic forecast (European Commission in March 2021))

| Indicators |

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

2022 |

| GDP growth (%, YoY) |

5 |

-2.9 |

2.8 |

5 |

| Inflation (%, YoY) |

2.3 |

-0.6 |

1.6 |

2.2 |

| Unemployment (%) |

4.4 |

6.8 |

7.9 |

6.3 |

| General government balance (% of GDP) |

0.1 |

-4.9 |

-5.6 |

-3.3 |

| Gross public debt (% of GDP) |

8.4 |

18.2 |

21.3 |

24 |

| Current account balance (% of GDP) |

1.9 |

-1 |

1.9 |

1.7 |

Currently, the emphasis has been placed on acceleration of digitalisation, both in the private and public sectors. Digitalisation is one of the priorities of all national strategies, European funding (ESF RRF, etc.) and Estonian government budgets. According to the Council of the European Union, country-based recommendations should focus on investment in the green and digital transition, in particular on the digitalisation of companies in Estonia in 2020–2021[10].

Education Strategy 2021-2035[11] targets:

- The plan is to provide 100% of basic school graduates with basic ICT skills, up from 83% today.

- A total of 60% of the population aged 16-74 should acquire digital skills above the basic level, up from 35% today.

- Digitalisation of methodology of teaching and learning (target levels to be developed)

There are no specific digitalisation targets in the Research and Development, Innovation and Entrepreneurship Strategy[12]; however, the whole strategy is horizontally based on or supporting digitalisation and contains specific activities, such as:

- fostering automation in enterprises through the development of a roadmap for digitalisation and the financing of the investments included in this roadmap, including support for digitalisation and the adoption of AI and robotics technologies to improve the efficiency of enterprises’ processes and supply chains, and to increase the added value of products and services;

- reducing administrative burdens on businesses, including by providing public services to businesses through a single digital gateway, as proactively as possible and in line with their business developments, and by encouraging the development and implementation of the real economy;

- fostering digital commerce (e-commerce, platform economy, sharing economy) and the circular economy to improve the competitiveness of Estonian micro, small and medium-sized enterprises in international trade;

- developing and expanding the e-Residency programme to invite new undertakings to do business in and through Estonia;

- continuing the implementation of the Work in Estonia programme to attract professionals needed by Estonian businesses, and developing an efficient inter-professional talent policy;

- supporting the use of the best available technologies in industrial enterprises and encouraging the adoption of business models based on modern technologies, including the diagnosis and auditing of bottlenecks and the involvement of internationally experienced experts and professionals from abroad;

- fostering the growth of exports of existing RDI-intensive products and technologies developed in Estonia and creating the conditions for the development and sale of new products and services in higher added value sectors and markets, supporting companies through quality infrastructure services and helping them to obtain the necessary certificates and marketing authorisations in the target market, encouraging cooperation and joint activities between companies to increase export volumes.

Most important digitalisation projects in the member state:

- Leveraging reuse in digital governance is a reality. A common digiriik.eesti.ee information space has been created, providing a clear overview of the development principles of digital governance and a systematically managed collection of problems and solutions for digital governance, and platforms for the reuse of ICT components have been implemented: the software selection available in the digital governance code repository has been expanded, and a repository has been created for the sharing of AI toolkits and other reusable technical components.

- The aim for 2021 is to draw up a new national AI/machine learning plan and to continue implementing the plan in the coming years.

- By the end of 2022, the KrattAI strategy will be adopted in at least five government authorities.

- Implementation of activities in accordance with the established Open Data Action Plan 2021–2022 and Data Management Action Plan 2021–2022.

- To ensure the sustainability of digital governance, we coordinate the use of the state budget as well as EU funds (SF and RRF) to secure funding for the IT developments that are important for the state and to provide a boost for digital transformation. A major focus in 2022–2023 will be on developing implementation schemes for EU funds (SF 2021–2027; RRF until 2026) and on establishing coordination routines. A number of state-wide reforms will be launched, including a new level of public digital services (making services holistic and proactive) and a new level of digital infrastructure, including a secure digital cloud.

- We will update the national concepts for cyber security management and for resolving cyber incidents. Based on these concepts, we will supplement the Cybersecurity Act and other legislation and regulatory documents setting out the roles, responsibilities, tasks and cooperative relationships of authorities and organisations.

- We will raise situational awareness of cyber security trends, threats and impacts and develop the capacity to create adequate cyber security measures. To this end, we will systematise the R&D processes on cyber security and will commission the necessary analyses and studies.

- We will adopt a new cyber and information security standard and improve our capacity to implement security measures. We will create a system of metrics to monitor and measure the level of national cybersecurity.

- One of the outcomes of smart development of existing and new information systems should be increased satisfaction with public services among citizens and businesses. This is to be achieved, among other things, through the introduction of proactive government services, which will also include the development of eesti.ee and integrations of the State Budget Strategy 2022–2025 and the 2021 Stability Programme. Seventy-five integrations with the rest of the government’s databases and services. In addition, support will continue to be provided for the development of public services and basic infrastructure, and for the interoperability of public services.

- Active development of proactive government services will be launched, based on the roadmap for the development of proactive government services agreed in September 2020, with the first developments planned to start in the fourth quarter of 2021. A total of 14 proactive government services have been agreed under the roadmap and 9 of these services will be developed in the period 2021–2025.

- The introduction of better public service management, including measurement and monitoring, will continue. This will be done by developing a common service standard for the design, development, management and measurement of services, by further developing the knowledge and skills of service managers and owners, and by creating and providing tools for service owners to manage the services, including by improving user-friendliness of the national central directory of services.

- The support measure for passive broadband infrastructure for access networks concluded with Elektrilevi in 2018 will be completed, which should provide 40,016 addresses in rural areas with access to a high-speed access network (EUR 11.6 million) by the end of 2023.

- State support will be used to establish the first continuous 5G transport corridors and 5G areas in residential and industrial areas.

- Additional support measures will be launched to support the establishment of access networks in the failing areas of the market.

2. National framework of digitalisation and collective bargaining

- Legislation, strategic documents, institutional framework, opinions of national social partners, collective labour agreements, etc.

Generally, collective bargaining on the company or sectoral level is quite rare in Estonia and most work life issues and related matters are regulated in law. Only around 4% of employees are members of trade unions and the coverage is concentrated in specific public sector jobs (teachers and medical workers) and transport. There is a trade union for the service employees of two big telecom companies, but no trade union in the ICT sector representing ICT specific jobs. There is a collective agreement at the confederation level to adopt the European Social Partners Framework Agreement on Digitalisation. The members of the Estonian Employers’ Confederation have also responded in the survey that they would prefer most of the social dialogue to take place at the level of central unions and the government[13].

Collective bargaining is mainly regulated by the Collective Agreements Act[14].

The most important strategies on digitalisation at the national level are ‘Estonia 2035’[15], ‘Estonian Digital Society 2030’ (to be approved in 2021), the Research and Development, Innovation and Entrepreneurship Strategy 2035 (TAIE), and the Education Strategy 2021–2035. The general targets partially related to digitalisation in these strategies include:

- Labour productivity is 110% of the average of the 27 European Union Member States.

- R&D expenditure in the private sector is 2% and in the public sector 1% of GDP.

Estonian digital society 2030[16] targets:

- Based on the vision, the main objective of digital society development in the next decade is increasing Estonia’s ‘digital power’: gaining the best experience for digital governance, providing ultra-fast internet for everyone, and ensuring safety and credibility of our cyberspace.

As a result, satisfaction with public digital services among individuals and businesses is expected to rise from 69% in 2020 to 90% in 2030, availability of high-speed internet from 47% to 90%, cybersecurity rating from 58% to 100%, and credibility should be maintained at 96%.

- Satisfaction with public digital services should rise from 47% among businesses and from 69% among private individuals in 2020 to 90% in both groups by 2030.

- The share of households and businesses in Estonia with access to at least 100 Mbps internet, which can be upgraded to 1 Gbit/s, is expected rise from 58% in 2021 to 100% by 2030.

- Cybersecurity: minimising the proportion of 16-74-year-olds who have not interacted online with public authorities or service providers in the last 12 months due to security risks.

National strategies and development plans are generally reflected in government action plans, but do not always necessarily deliver results. Business organisations therefore have an important role to play in both designing development plans and ensuring their implementation.

The most visible manifestations of digitalisation in the context of employment are probably the expansion of teleworking opportunities and the increasing need for digital skills. Teleworking is regulated in the Employment Contracts Act[17] and the employer-employee liability for teleworking is specified in the social partners’ agreement on teleworking, on the basis of which the Ministry of Social Affairs has also drawn up a guide on teleworking[18].

In Estonia, several studies have been carried out on forms of work facilitated by digitalisation (platform work, telework, etc.):

- Heejung Chung. Future of work and flexible working in Estonia. The case of employee-friendly flexibility, 2018[19].

- Johanna Vallistu jt. Analüüs ‘Tuleviku töö – uued suunad ja lahendused’ [Analysis. ‘Work in the future – new trends and solutions’], 2017[20].

- The Foresight Centre has carried out a series of studies, with a focus on the future of work:

- Platvormitöö Eestis 2021 [Platform Work in Estonia 2021][21].

- Understanding Virtual Work. Prospects for Estonia in the Digital Economy, 2018[22].

- Tööturg 2035. Tööturu tulevikusuunad ja -stsenaariumid [Labour Market 2035. Future Labour Market Trends and Scenarios], 2018 [23].

A good overview of digitalisation can be found in:

- European Digital Economy and Society Index (DESI)[24]

- IMD Digital Competitiveness Ranking[25]

3. The role of social partners

- State of play on the main issues, arranged by the FAA on Digitalisation

- Challenges and opportunities faced by social dialogue deriving from the digital transformation of the world of work

- Examples of good practice

3.1. State of play on the main issues, arranged by the FAA on Digitalisation

On 29 March 2021, the social partners agreed on an Estonian social partners’ action plan for the implementation of the European Social Partners Framework Agreement on Digitalisation. According to the agreement, the Estonian Confederation of Trade Unions and the Estonian Employers’ Confederation recognise the European ‘Framework Agreement on Digitalisation’ and consider it applicable in Estonian conditions. The social partners will discuss the implementation of the action plan at bilateral meetings and, if necessary, supplement it with new actions. The partners will report to the European Social Dialogue Committee on the implementation of the agreement on the Framework Agreement on Digitalisation.

The social partners discussed the possibilities for implementing the Framework Agreement at a bilateral meeting on 4 February 2021, and decided to draw up the following action plan:

- Joint activities:

- Adaptation of the 2017 telework agreement[26].

- The partners will collect and discuss members’ opinions in September 2021.

- Setting up of a joint working group in September 2021.

- Discussion/agreement on the right to disconnect in October 2021.

- Funding/promotion of digital training in the Unemployment Insurance Fund in April 2021[27].

- Participation in the working groups on national policy development (ongoing activity):

- Council for Adult Education;

- Supervisory Board of the Unemployment Insurance Fund;

- OSKA Coordination Council[28].

- Estonian Trade Union Confederation

- Google project: helping employees adapt to digitalisation and process management – 2021-2022.

- Discussion of the Framework Agreement on Digitalisation at the annual autumn conference of the ETUC to identify possible implementation actions in sectoral and company level collective agreements – September 2021.

- Estonian Employers’ Confederation

- Mapping the needs, opportunities and impact of the digital transformation, and making relevant recommendations for 2022 to employers and the government.

- Digital transformation activities in working groups.

As of June 2021, the Estonian Employers’ Confederation, for example, together with the Estonian Association of Information Technology and Telecommunications, has organised a 4-part series of workshops on the ‘Practical Digital Journey of a Company’[29] for business leaders who want to take their production or service provision to the next level with the help of digital technologies. We also contributed to the design of a national support measure for the creation of a digitalisation roadmap[30] for businesses. Previously, we carried out a project to provide business leaders with basic digitalisation skills[31].

The Estonian Employers’ Confederation has spent a great deal of energy on the adequate design of the national mitigation measures for the COVID19 crisis and the REACT-EU, Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF), as well as other European measures with a similarly strong emphasis on digitalisation.

3.2. Challenges and opportunities faced by social dialogue deriving from the digital transformation of the world of work

The primary challenges posed by digital technologies are likely to be the rapid growth of inequality and the digital gap, with many enjoying the benefits of digital services and skills while the rest of society lacks the ability to take advantage of them. For more qualified people and more innovative employers, digital technology creates new opportunities to earn and become more competitive. It is becoming increasingly difficult for people without basic digital skills and for companies not investing in digitalisation to stay competitive. At the same time, digital technology also creates better opportunities for lower-skilled people to participate in training, find and apply for job vacancies, work remotely, etc., if they so wish. For employers, digitalisation creates opportunities to reduce labour intensity and increase efficiency. Trade unions and employers can sometimes have different views on possible solutions to the problems. Employers believe that transfers/subsidies can only play a temporary role in reducing inequalities and increasing competitiveness. Subsidies should be channelled towards skills and innovation, including digitalisation, rather than compensating for income disparities.

The second major, and more practical, category is the set of problems associated with the rise of teleworking. Employers find it harder to maintain organisational culture, control and team spirit with remote workers. Employees complain more about communication barriers, stress and confusion regarding working and rest time. In addition to working time, there is confusion over the allocation of tools, resources and responsibilities between employee and employer.

According to a survey,[32] the following have been identified as the disadvantages of ICT-based telework, which are also likely to be encountered by the social partners in their dialogue:

- the risk of blurring the boundaries between work and family life, and the stress this can cause;

- the risk of overwork;

- the risk of increased social isolation;

- the occasional risk of increased control by the person providing the work;

- the risk to the employees’ health, if employees do not manage their own working conditions;

- the potential for losing control over the time an employee devotes to work;

- security risks;

- a potential loss of the sense of unity within the organisation;

- management requires more energy and attention;

- the person providing the work cannot verify that health and safety requirements are being met.

The following have been identified as the key weaknesses and threats of digitalisation of industry[33]:

- The key challenge in the Estonian economy remains the digitalisation of companies. Although most companies use automated data exchange for receiving orders from customers and use two or more social media platforms, e-commerce in companies could be improved.

- Regarding connectivity, fixed broadband coverage is very low (partially compensated by mobile coverage), as is the take-up of ultrafast broadband.

- Estonia’s performance in the supply and demand of digital skills shows significant room for improvement because of poor ICT skills among employees.

- A substantial number of companies encounter problems finding skilled employees.

- Lack of awareness and the knowledge of necessity to take up digital technologies and their benefits among managers/owners of companies.

- Lack of corporate strategic planning.

- The regulatory framework in Estonia still needs to be reviewed and adapted to the digital age.

- Many pillar-specific initiatives have been launched only within the last year. Their real impact still needs to be seen.

- Companies are slow to embrace digital technologies due to a lack of use cases, success stories and lighthouse projects.

Thus, most of the challenges related to digitalisation concern the communication of digital skills, the need and opportunities for digitalisation, and regulatory gaps. Most of these can probably also be addressed in social dialogue at the level of central unions.

3.3. Examples of good practice

This subsection highlights some good practice examples of social partners working together on digitalisation and modern industrial relations.

The first example is the drafting of a telework agreement and manual. The Occupational Health and Safety Act[34] places the responsibility for creating and ensuring a safe working environment for health on the employer in all cases, but in practice it is almost impossible for employers to ensure safe working conditions outside their own place of business. However, working in home offices, cafés, libraries and elsewhere using digital tools is becoming more common. On 25 May 2017, the Estonian Employers’ Confederation and the Confederation of Estonian Trade Unions signed an agreement on teleworking which, among other provisions, set out the principles for ensuring occupational health and safety in the case of teleworking. On the basis of the social partners’ agreement on telework, the Ministry of Social Affairs has prepared a manual[35] for flexible implementation of the Occupational Health and Safety Act in telework situations. The content of the manual was seen by employers as an optimal compromise until the coronavirus crisis, but the much more widespread use of telework in 2020 resulted in the resurfacing of certain questions that have perhaps not been adequately addressed in the telework manual. This includes, for instance, a reasonable division of working time, rest time and home office costs, where the current law allows for one or the other solution, but where either employers or employees have asked for more clarity.

The social partners also cooperate in the OSKA Coordination Council and the Supervisory Board of the Unemployment Insurance Fund. OSKA is a skills and labour demand forecasting system where a group of experts and analysts assesses the future demand for specific skills and specialists, and the adequacy of current training supply. As early as 2016, OSKA’s results indicated that the greatest areas of shortage in Estonia include various digital skills and ICT specialists.

The Unemployment Insurance Fund has also invested heavily in recent years in active labour market measures and in making the skills needed on the labour market more accessible. The share of clients of the Unemployment Insurance Fund participating in training or other qualification raising services was 70% in 2019 and 67% in 2020. The total number of people participating in training funded by the Unemployment Insurance Fund was 106,000 in 2019 and 111,000 in 2020[36]. A total of 11% of all unemployed participants attended a training on digital skills.

Among other things, the social partners agreed in 2017, working in the Supervisory Board of the Unemployment Insurance Fund, on commencement of financing to prevent unemployment[37]. The services to prevent unemployment include: 1) support for participation in formal education for a worker or a registered unemployed person who is taking up vocational training, higher vocational education or higher education in an undergraduate programme; 2) labour market training for workers who are at risk of unemployment and have a training card; 3) qualification support service for workers who have completed training using labour market training or training support facilities; 4) training support for employers to develop the knowledge and skills of workers in taking up employment and adapting to changes in the employer’s business. In order to prevent unemployment, the employee or the employer can receive financial support for attending a training course included on the list of the Unemployment Insurance Fund or for participating in formal education. A total of 4% of workers who wanted to prevent unemployment opted for digital skills training in 2020.

From 2021, the Unemployment Insurance Fund will additionally compensate up to EUR 2500 per employee, if the employer sends the employee to digital skills training.

[1] Statistics Estonia and Eurostat have been used as sources throughout this chapter.

[2] https://www.eas.ee/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/T%C3%B6%C3%B6stuse-digitaliseerimine_aruanne-Tootmisprotsessidejuhtimisedigitaliseeriminet%C3%B6%C3%B6stuses.03.2020.pdf

[3] 27 countries from 2020 (Eurostat 07.06.2021)

[4] Statistics Estonia and The Digital Economy and Society Index (DESI): https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/policies/desi.

[5] https://www.stat.ee/et/uudised/koroonakriisi-tulemus-200-000-kaugtoo-tegijat, 21.06.2021

[6] https://turundajateliit.ee/89-tootajatest-soovib-tulevikus-jatkata-osalise-kaugtooga/

[7] https://www.stat.ee/et/uudised/koroonakriisi-tulemus-200-000-kaugtoo-tegijat, 21.06.2021

[8] https://www.stat.ee/et/uudised/koroonakriisi-tulemus-200-000-kaugtoo-tegijat, 21.06.2021

[9] https://www.stat.ee/et/uudised/koroonakriisi-tulemus-200-000-kaugtoo-tegijat, 21.06.2021

[10] https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?qid=1591720698631&uri=CELEX%3A52020DC0506

[11] https://www.hm.ee/et/kaasamine-osalemine/strateegiline-planeerimine-aastateks-2021-2035/eesti-haridusvaldkonna-arengukava, 18.06.2021

[12] https://www.hm.ee/et/TAIE-2035, 18.06.2021

[13] Inaugural survey of the Norway Grants-funded project ‘Social Partnerships and Flexible Labour Relations’, April 2021.

[14] https://www.riigiteataja.ee/en/eli/ee/518062018002/consolide/current,

[15] https://valitsus.ee/strateegia-eesti-2035-arengukavad-ja-planeering/strateegia, 18.06.2021

[16] Approval of ‘the draft: ‘Estonian Digital Society Development Plan 2030’, https://eelnoud.valitsus.ee/main/mount/docList/e00fb8a2-9c4b-42b6-b424-7e320949db98, 18.06.2021

[17] https://www.riigiteataja.ee/akt/112072014146?leiaKehtiv

[18] Both the manual and the social partners’ agreement are available as of 21.06.2021 at: https://www.tooelu.ee/et/131/tooohutus-kaugtool.

[19] https://www.riigikogu.ee/wpcms/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/Employee-friendly-flexibility.pdf

[20] https://skytte.ut.ee/sites/default/files/skytte/tuleviku_too_lopparuanne.pdf

[21] https://www.riigikogu.ee/wpcms/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/2021_platvormitoo_uuring.pdf

[22] https://www.riigikogu.ee/wpcms/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/Virtual-work-size-and-trends_final1.pdf

[23] https://www.riigikogu.ee/wpcms/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/tooturg_2035_tooturu_tulevikusuunad_ja_stsenaariumid_A4_veeb.pdf

[24] https://ec.europa.eu/newsroom/dae/document.cfm?doc_id=66911, 30.06.2021

[25] https://worldcompetitiveness.imd.org/countryprofile/EE/digital, 30.06.2021

[26] The telework agreement was concluded to clarify responsibility for health and safety in telework situations. While the employer is responsible for safety and working conditions in the workplace, the manual states that, when working remotely, the employee is responsible. The employer has a duty to inform and consult the teleworker about possible risks.

[27] Peep Peterson, the head of the Estonian Trade Union Confederation, was the chairman of the Unemployment Insurance Fund from May 2020 to April 2021, and Arto Aas, the CEO of the Estonian Employers’ Confederation, holds the position from May 2021.

[28] OSKA – a project running since 2016 for analysing the needs for labour and skills necessary for Estonia’s economic development.

[29] https://itl.ee/toostus-4-0/digiteekond/

[30] A digitalisation roadmap is a strategic document for a company to assess the impact of digitalisation, the investments needed to achieve the objectives, their cost-effectiveness, and the timeframe. The digitalisation roadmap highlights the bottlenecks in technological processes and the terms of reference for tackling at least one of those bottlenecks. https://www.eas.ee/teenus/digiteekaart/

[31] DigiABC project – ‘Estonian Information Society Development Plan 2014-2020’ has set the target of reducing the share of non-users of computers and the internet to 5% by 2020. The DigiABC project supports the achievement of this target and provides an opportunity to acquire digital literacy, which in turn supports people of working age becoming members of the information society and increasing their individual competitiveness and the competitiveness of sectors that are important for the Estonian economy.

[32] Vallistu jt. Analüüs ‘Tuleviku töö – uued suunad ja lahendused’ [Analysis. “Work in the future – new trends and solutions”], 2017: https://skytte.ut.ee/sites/default/files/skytte/tuleviku_too_lopparuanne.pdf, 21.06.2021

[33] Monitoring Progress in National Initiatives on Digitizing Industry. Country report. European Commission, 2019.

[34] Occupational Health and Safety Act, https://www.riigiteataja.ee/en/eli/522042021002/consolide, 21.06.2021

[35] Both the manual and the social partners’ agreement are available as of 21.06.2021 at: https://www.tooelu.ee/et/131/tooohutus-kaugtool.

[36] The size of the economically active population in Estonia’s labour market was 687,800 people in 2019 and 689,900 in 2020.

[37] https://www.tootukassa.ee/content/teenused/toota-ja-opi, 21.06.2021.

Δεκ 26, 2021 | Research

STAGE 1

Table of Contents

1. Historical Trends and Development of Digital transformation in the partner country

1.1. The structure of the economy in Bulgaria

1.2. Recent developments

1.3. Forecasts and the future developments

2. National framework of digitalization and collective bargaining

3. The role of social partners

3.1. State of play on the main issues, arranged by the FAA on Digitalisation

3.2. Challenges and opportunities faced by social dialogue deriving from the digital transformation of the world of work3.3. Examples of good practice

1. Historical trends and development of Digital transformation in the partner country

1.1 The structure of the economy in Bulgaria[1]?

Gross Domestic Product (GDP) at current prices for the first quarter of 2021 is 27 054 million BGN (preliminary data). GDP per person is 3 912 BGN. In Euro, GDP reaches 13 833 million EUR in total and 2 000 EUR per person. Seasonally adjusted data show a decline of 1.8% compared to the first quarter of 2020 and an increase of 2.5% compared to the fourth quarter of 2020.

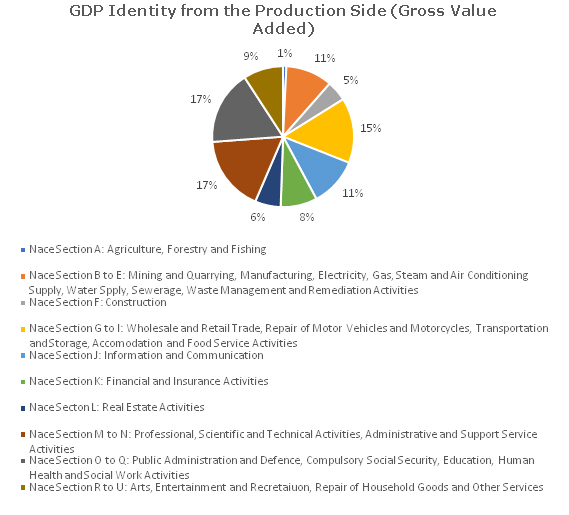

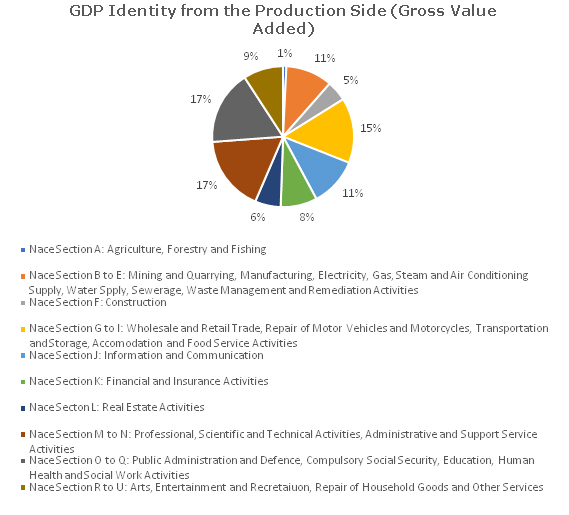

The highest contribution (21.7%) to the Gross national value-added in 2020 is made by the Sectors B-E (Mining and quarrying; manufacturing; electricity, gas, steam and air conditioning supply; water supply; sewerage, waste management and remediation activities). The most contributing sectors G-I (Wholesale and retail trade; repair of motor vehicles and motorcycles; transportation and storage; accommodation and food service activities) and O-Q (Public administration and defense; compulsory social security; education; human health and social work activities), represent 19.0% and 17.1% of the Gross value added (GVA) in 2020. The Agriculture, forestry and fishing sector amounts to 3.9% of the GVA. The Information and communication sector formed 8.0% of the national GVA in 2020.

There were 419 681 non-financial enterprises in 2019. When grouped by size, the micro-enterprises (0-9 employed) dominate in number (388 980 or 92.7% of all non-financial enterprises), followed by the small enterprises[2] (25 204 or 6.0%) and medium enterprises[3] (4738 or 1.1%). The large enterprises represent only 0.2% of all non-financial enterprises in 2019. The small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) can be referred to as the backbone of the Bulgarian economy, providing a potential source for jobs and economic growth. When grouped by economic activity, the non-financial enterprises are concentrated unevenly across the economy. The NACE sections where most of the enterprises can be found include Wholesale and retail trade; repair of motor vehicles and motorcycles (34.2% of all non-financial enterprises operate in the sector); Professional, scientific and technical activities (11.5% of all non-financial enterprises); Manufacturing (7.5% of all non-financial enterprises); Accommodation and food service activities (6.5% of all non-financial enterprises); Real estate activities (6.0% of all non-financial enterprises).

The official statistics for the first quarter of 2021 reveal 3 million employed persons and 204 thousand unemployed persons. Respectively the employment rate was 51.4%[4] Despite the low unemployment and the targeted employment policy of the government, 25.0% of the industrial enterprises pointed out the labour shortage as a factor limiting their activity (data provided by the national statistics business inquiries in June 2021). And the unemployment rate was 6.3%. The shrinking labour supply, along with the pandemic government support measures and the increase of high-qualified workers, contributed positively to the remuneration level nationwide. The total hourly labour cost rose by 4.9% compared to the first quarter of 2020. In March 2021, the average wage and salary was BGN 1 500 and rose by 4.8% compared to the previous month and by 13.6 % compared to March 2020.

Digital penetration and development are being analyzed by different stakeholders in the country. Data indicates that Bulgaria has large numbers of artificial intelligence (AI) players across the industry as well as energetic and indigenous private sector successfully competing internationally in areas such as machine-building and IT. According to the 2019 InnovationShip survey by the EDIT network of digital Bulgaria, the most crucial segments of the emerging deep tech in Bulgaria include platform building, big data analytics, machine learning and AI, cloud computing, automation systems, blockchain/API and Connectivity/IoT. According to the data of the Bulgarian Association of Software Companies (BASSCOM) the average compensation of the software sector employees remains three times higher than the national average, and when (adjusted through PPPs) remains even higher than compensation of their colleagues in the UK and Germany.

Since 2013 the ICT sector as a percentage in the national GDP has constantly been increasing and reached 6.1% in 2018. At the same time, the ICT personnel in total employment is just 2.85%. Compared with advanced EU economies, Bulgaria registers a high rate of business expenditure on Research and Experimental Development (R&D) in the ICT sector as % of total R&D expenditure.

Enterprise data indicates that almost all (95.5%) enterprises have access to the Internet. Despite the increase in the share of enterprises providing company portable devices that allow mobile internet connection, Bulgaria is still quite below the EU average rates of employees equipped with such devices. About half (48.0%) of the enterprises still do not have their own website, and even few use paid cloud computing services (10.9%) or performed big data analysis (6.3%).

The country is still below the EU average when security is concerned: enterprises with formally defined ICT security policy (19% of Bulgarian enterprises compared to 31% in EU 27 in 2015); enterprises which made persons employed aware of their obligations in ICT security-related issues (51% in Bulgaria, 61% in EU 27 in 2019); enterprises using any ICT security measure (85% in Bulgaria, 92% in EU 27 in 2019); enterprises having insurance against ICT security incidents (3% in Bulgaria, 21% in EU 27 in 2019).

About half of the Bulgarian SMEs still do not have an innovation strategy in place. About one-third of the SMEs report that personnel have no digital skills at all, and 38% report difficulties in finding employees with any digital skills. SMEs still encounter problems in finding information on digital projects/programs, applying digital marketing tools, allocating funds on the digital transformation of the business processes (BCCI data for 2019).

Official data concerning the digitalization of society indicates that 78.9% of Bulgarian households have access to the Internet at home; however, there are still significant regional disparities in terms of access. 69.2% of the Bulgarians report using the Internet regularly (every day or at least once a week), but the highest share of the indicator is within the youth group (up to 35). Still, 20.9% of the Bulgarians have never used the Internet (in contrast, the EU 27 average is 9%). Many digital skills are underdeveloped. For example, Bulgarians still find difficulties in installing and using different software products/apps.

Training initiatives related to acquiring (digital) competencies have been organized over the years by both public and private sector entities. Special attention is paid to the women, vulnerable youths and young children so that a wider audience is reached and equal access to training is guaranteed. The higher education programs have been currently paying interest in digital industrial technologies, and there are already available studying opportunities. As to public administration employees, the Bulgarian Institute of Public Administration (IPA) provides training using modern technologies, methods and programs. Data show that just in the first half of 2021, nearly 11 000 public administration servants have participated in IPA training.

Despite the active government policy related to the digital transformation of the economy, Bulgaria still occupies the bottom position within different international rankings. The 2020 IMD World Digital Competitiveness Ranking positioned Bulgaria in 45th place among 63 researched economies. According to the 2020 Digital Economy and Society Index (DESI), Bulgaria performs quite under the EU average and currently has the lowest score on the index.

- Forecasts and future developments

According to a McKinsey report, digitization can be the next big engine for sustainable growth for Bulgaria, adding 1% extra growth per year to the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) of the country by 2025.

Harnessing even more significant digital opportunities requires decisive policy interventions. To strengthen Bulgaria’s digital status, future efforts need to be channeled in the following areas:

– building skillset for the future by developing a wide-ranging reskilling strategy, updating youth education for the future and actively counteracting brain drain;

– individuals should prepare for the digital economy and invest in lifelong learning;

– investments in human capital through both primary and secondary education are a significant step towards the economy’s digitalization. Digital and soft skills for the general population need to be developed. Private and public education efforts should be coordinated and build on each other. Furthermore, training should encounter population groups prone to exclusion (such as females, ethnic minorities, etc.) and ensure the dissemination of cost-efficient technological devices;

– technology adoption in the public sector (e.g. speeding up the development of online public services and their adoption);

– technology adoption among businesses (e.g. promote digitization benefits and digital transformation).

The private sector should embrace a pro-digital organizational culture. SMEs are exposed to high competition but do not have enough human, financial and technical capital to maintain and increase their competitiveness in the context of the digital transformation. Since SMEs still lack financial resources to integrate digital instruments into their business processes, improving the legal framework for digital and digitally-driven SMEs is a must. Measures may be aimed at funding, provision of simplified e-services and lower taxation.

– Strengthening regional cross-border digital collaboration (e.g. create a strong digital pillar within regional collaboration platforms)

– Further, stimulate the startup ecosystem through, e.g. improving entrepreneurial talent pool and increasing access to capital).

– Overcoming labour market shortages.

Companies declare that software engineers and developers are the hardest to find; talent shortage is encountered. Strengthening business-education relations can contribute to sparking interest in ICT and STEM disciplines among students. Comprehensive research on the inclusion barriers (prejudice, lack of skills, unattractiveness, etc.) may support the process.

2. National framework of digitalization and collective bargaining

2.1. Strategic framework

Bulgaria has adopted various strategies related to digital transformation. The first National Programme “DIGITAL BULGARIA 2015” was approved in 2012. It identifies seven interrelated priority areas: 1. A vibrant digital single market; 2. Interoperability and Standards; 3. Trust and Security; 4. Fast and Ultra-fast Internet Access; 5. Research and Innovation; 6. Enhancing Digital Literacy, Skills and Inclusion; 7. ICT-enabled Benefits for EU Society

Before that a number of strategic and program documents have been developed, covering partially the topic of digitalization: National Reform Programme 2012-2020 (Development of e-Health; Development of e-Government; Broadband development; Promoting investments aimed at creating new jobs in high-tech industries and knowledge-based services (education, R & D, ICT, etc.).; ICT for Energy Efficiency; ICT to improve the Education system), National Strategy for Scientific Research 2020 (the main emphasis is on supporting research and technological development in the fields of research, ICT infrastructure, e-Government, online health, smart home, digital skills, security in cyber-space), Innovation Strategy of Bulgaria, National Strategy for Broadband Access Development, Common Strategy for e-Government Development 2011-2015. In December 2019, the Council of Ministers adopted an updated National Program “Digital Bulgaria 2025”.

The situational analysis provided in National Program “Digital Bulgaria 2025” gives an overview on some main domains, related to the scope of the TransFormWork project:

Human resources:

The overall level of digital skills in Bulgaria is among the the lowest in the EU: the proportion of people with at least basic skills in the field of digital technologies amounts to around 29%, while on average for the EU this share is 57 %. This trend was also confirmed among young people: 54% of young people between the ages of 16 and 24 have at least basic digital skills (relative to the EU average of 81 %). People with more advanced user skills (above basic digital skills) accounted for 11% of the total number of less than one-third of the EU average. There have also been policy changes – the education system is in the process of reforms at all levels, and although the measures are not fully in line with the with the scale of the digital transformation, however, the focus on improving digital skills. In the context of higher education reform, measures have been taken to strengthen cooperation between educational institutions and businesses.

Using Internet services:

Although it has improved its performance, Bulgaria is below the average level in internet services: 64% of citizens use the internet (in the the EU average is 83%), while 27% have never used it – this is the highest value across the EU. Among EU internet users Bulgarians make the most video calls; they are well above the average level and in terms of social networking activity (79% of the total number of compared to 65%). There are significant differences for regular internet users in education – 89.6% of persons with higher education and 37.7% of persons with primary or lower education regularly use the global network. Employment status also affects the activity of the population in the global network. The most common use of it is those in education (unemployed), 98.6% of who surf regularly and in the case of workers (employed and self-employed) the relative share is 80.8%. Almost half of the unemployed (45.1%) also regularly used on the internet.

Deployment of digital technologies

The adoption of digital technologies by businesses in the Bulgaria is going slowly. In recent years, there has been a gradually evolving ecosystem of digital and technological entrepreneurs, but investment in the digitisation of the economy is still limited. These insufficient investments, together with the shortage of ICT professionals, are defined as possible reasons for slower digitisation in Bulgaria compared to other Member States.

Bulgarian businesses are facing difficulties to use the opportunities provided by online trading: 6% of the total number of SMEs sell online (compared to 17% on average in the EU), 3% of all SMEs make cross-border sales and only 2% of their turnover is from online trading.

Although Bulgarians use social media intensively for personal use, only 9% of businesses use them for personal use compared to 21% on average in the EU. Finally, the the number of enterprises with a high intensity index represent only 7.81 % of all enterprises. It is positive that 23% of companies share information online, with an average of EU 34%.

The insufficient digital, communication and entrepreneurial skills of the citizens and deepening the problem of the shortage of a highly skilled workforce in high-tech activities is barriers to the development of the digital economy. According to the government, a strategically coordinated approach involving all stakeholders is needed to ensure an update of the programmes for the digital skills at all levels and parts of the educational system, additional qualification and retraining of employees and unemployed, an increase in the number of graduates in the field of accurate science, technology, engineering and mathematics (TNTIM), inclusion of employers in vocational training, reducing the digital economy and reducing the division with a focus on disadvantaged social groups. The use of ICT in industry and services involves the deployment of ICT applications to optimise the management, production and processes, e-commerce and e-business, the provision of interactive online services, increased opportunities for flexible, flexible and remote and part-time work, etc. The low level of investment of enterprises in ICT limits Bulgaria’s ability to benefit from the benefits of the digital economy.

2.2. Social dialogue and collective bargaining

Social dialogue

Digitalization is at the focus of social partners in recent years. In 2010 all nationally representative organisation of employers and workers concluded a national agreement, arranging telework. This agreement was based on the 2002 EU Social Partner Autonomous agreement on telework[5] Based on the agreement and on joint request by the social partners, the Labour code was amended. With these amendments a new section was introduced to arrange telework. Despite that, according the Eurostat, for the period 2011-2019, the percentage of employed people working from home on a regular basis, varies from 0.2 to 0.6.[6] The percentage, reported for the pandemic 2020 is 1.2 – again the lowest rate for 2020, compared to EU 27 – 12 %

In 2019 and 2020, the Economic and social council[7] adopted three opinions, related to digital transformation – challenges faced by workers and businesses in terms of digitalization, as well as challenges and opportunities for digital transformation in Bulgaria. All three opinions were elaborated by two co-rapporteurs – from the employers’ and workers’ side. Among the main conclusions we can highlight the following:

- the digital transformation and its impact on all social processes is an issue of strategic importance for developing economic potential, improving working conditions and quality of life, especially in the context of an ageing population, but at the same time confronts society with so far unknown risks;

- with the right policies in place, the opportunities for technological development could be used in an appropriate way, thus – reducing the risks to the minimum;

- the digital transformation, expressed through the introduction and use of modern digital technologies in the field of tangible and intangible production in order to increase the overall factor productivity and competitiveness of enterprises, leads to professional transformation;

- the digital transformation will require significant investments from the private and public sectors. The more these investments slow down over time, the more difficult it is to access finance, the more money each worker will need in the future to increase his productivity, and every entrepreneur to increase his competitiveness;

- the degree of technological advancement predetermines the productivity of the workers;

- substantive changes in the rules are needed in order to establish transparent and democratic rules for interaction between people and digital technologies;

- emphasizes the importance of digital skills and competencies to increase the ability to adapt human capital to changing demands of the workplace and labour market. The educational infrastructure will play a crucial role, which must provide conditions and opportunities for their acquisition. Тhe Bulgarian government should focus more efforts on measures to stimulate digital competence and digital culture from early childhood throughout working life;

- The development of the process of “lifelong learning” (LLL) precisely because of the rapid development of technology and the need for continuous retraining of the workforce. It is important for such a policy to be aimed at the pilot creation of sectoral qualification funds, where the social partners have a key role to play. According to ESC, the state and the social partners must offer and develop alternative forms of education (digital platforms, mobile applications, online courses, etc.).

Collective bargaining

Telework and digitalization is a new topic for discussion for social partners, when it comes to collective bargaining. Only in 2020 the collective agreement in education was amended in order to reflect the new realities, posed by Covid-19 and the need to switch to mandatory telework. Here we need to underline that as described above, the Labour code was amended based on the social partners’ agreement, providing extensive regulation of telework. For that reason, clauses in the sectoral collective agreements cover mainly issues, related to pay and digital tools available for teleworking. According to data provided by the National institute for arbitration and conciliation (also responsible for analyzing the collective bargaining arrangements) for the period 31.12.2017-31.08.2021 the number of collective agreements, covering telework is constantly growing, but still remaining rather law from 11 undertakings covering 566 employees in 2017 to 74 undertakings covering 5 668 employees in 2021 (60 in the education sector). On a sectoral level, there are just 2 collective agreements – in education and constriction sector.

The pandemic clearly had an impetus for this increase. However, the law number of bargaining on this issue can be explained to a large extent with the law use of telework in pre-Covid times as well as law level of use of flexible working arrangements. Now, as Covid imposed the mandatory use of telework, the topic is becoming more and more relevant for all companies, regardless of whether they bargain collectively or not.

3. The role of social partners

3.1State of play on the main issues, arranged by the FAA on Digitalisation

Digital Skills

Digital skills are identified by the social partners as one of the key components in the process of the digital transformation of the economy. The social partners joined their efforts to arrange a separate scheme for the social partners to be financed by ESF managed by the Ministry of Labor and Social Policy. Under the scheme “Development of digital skills”, the social partners launched joint projects in partnership with the Ministry of Labor in Bulgaria. The projects aim to develop, test and approves unified profiles of the digital skills of the workforce in Bulgaria for key professions in 97 out of 99 economic activities. They will focus on identifying the specific levels of digital skills of the workforce at the sectoral level, the specific deficits and supporting the acquisition of digital skills needed to perform daily work tasks. The definition of digital competence levels must be in line with the European DigComp2.1 framework. Other activities that will be supported are the development, testing and testing of non-formal learning programs for the development of specific digital skills. The duration of the project is two years with the financial support of the ESF.

Modalities of Connecting and Disconnecting

There are no specific rules neither in legislation nor in collective bargaining covering the modalities of connecting and disconnecting. The general working time rules apply as it is expected that despite of new technologies entering progressively our lives in the recent decade, rights and obligations of employers and employees remain the same. The employers are obliged to respect the working time in all cases – this also covers telework. This is explicitly arranged in the Labour code.

There are no regulations on the possibility to use digital tools for private purposes during the working time. These issues are left to be regulated at a company level and might also be subject to collective bargaining. Here again the general requirement applies, that the workers need to perform the task he is assigned to during the working time.

Issues, related to overtime and its pay are also covered the the Labour code.

The other issues, covered by the Digitalisation agreement, such as culture that avoids out of hours contact, alert and support procedures. prevention of isolation at work, are to a large extent part of companies’ HR policies

AI and guaranteeing the human in control principle. Respect of human dignity and surveillance

AI is not covered neither by legislation, nor by collective bargaining. With regard to Respect of human dignity and surveillance, the only provisions we have in place are those deriving from the GDPR regulation. Both topics are to explored by the social partners in the coming years where they have a role to play in establishing jointly recognised standards and tools to support their members.

- Challenges and opportunities faced by social dialogue deriving from the digital transformation of the world of work

Collective bargaining in Bulgaria is conducted only and branch/sector or company level. Only branch/sector organisations that are members of nationally representative employers or workers organisations are entitled to conclude collective agreements (CA). According to data, provided by National Institute for conciliation and arbitration, in the end of 2020, there were 1 608 collective agreements[8] in force, covering 411 354 employees out of 2 211 773 (in 2020). At the same time, the National statistical institute reports for 600 272 employees[9] (2018) out of 2 038 040 covered by collective agreements (NSI, 2021; p.266).

Despite digital transformation has been in the focus of nationally representative social partners, the topic is not really a hot issue in the collective bargaining at the sectoral level. Only since the Covid-19 outbreak there we few collective agreements were amended in order to reflect pay issues, related mainly to mandatory introduced telework. To our knowledge, none of the four topics of the Framework agreement of digitalisation is specifically covered by collective agreements on sectoral level. To some extent this can be explained by the fact that for many years, collective agreements cover mainly issues, already arranged by the labour legislation and there is lack of experience or interest of the social partners to extend the scope of these agreements to broader topics. On the other hand, as already explained above, there is a low digital penetration in many sectors of the economy, thus digitalisation is not a natural issue to be discussed between social partners. An important factor is also that many sectors where there are digital transformation processes are not covered at all by collective bargaining.

It will be exactly one of the main goals of this project to discuss with sectoral level social partners the possible actions that can be taken through collective bargaining.

Some Covid-19 telework developments

As a result of the Covid pandemic in 2020 the use of telework in the public sector has significantly increased, especially in the system of higher and secondary education. This led to a reorganization of the work process and helped to maintain employment and human health. In the private sector, many of the companies in Bulgaria also had to use digital technologies to improve the organization of work in order to preserve the employment in Covid -19 situation. The Labor Code was amended immediately after the declaration of state of emergency, and new texts were introduced in it, through which telework during a declared state of emergency or emergency epidemiological situation has become a mandatory form of organization of the work process.

Telework work created challenges in home environment:

- Computers/laptops, office equipment, consumables and utilities, internet connection (often slow connection speed) are often at the expense of the employee;

- The home internet connection cannot take the heavy load when parents and children work and study at home at the same time;

- Often there is no separate room in the home as a workplace in which to work quietly (children are at home – students are distance learning, kindergartens do not work, parents are forced due to Covid infection have moved to work remotely);

- In some administrations with departmental net connection/web-based systems, access is not allowed from external computers, such as personal / home ones, and this makes remote work impossible;

- Employees do not have access to their official mail for the above reasons. At the same time, there may be a ban on sending official documents by personal mail;

- Examples of good practice of social partners

- Bulgarian Chamber of Commerce and Industry (BCCI)

The BCCI, together with six other partner organizations, participate in the CVETNET project. The project aims at building the capacity of CVET (continuous vocational education and training) provider’s networks and its members in order to better adapt their organizations and trainers in supporting SMEs to reskill and upskill their managers and employees on intergenerational learning and adaptation to digital transformation. Up to 2021, BCCI participated in the “Supporting Knowledge Capacity in ICT among SME to Engage in Growth and Innovation” (SKILLS+) project. It aimed to advance public policies promoting information and communication technologies (ICT) skills among SMEs in rural areas helping them seize fully the opportunities offered by a digital single market and benefits of a digital economy. As part of the project “DIGITAL SMEs- Promoting SME contribution in the implementation of policies on digitalization of the economy”, BCCI conducted a national survey among 550 employers. The major share of surveyed employers represented the micro, small and medium enterprises, and thus valuable insights on digitalization processes were generated for small economic players.

- Bulgarian Industrial Association (BIA)

BIA currently participates in the “Upskilling Lab 4.0” project, co-funded by the European Union’s Erasmus+ Program. Through international collaboration, the project aims to provide skills improvement opportunities to companies’ staff (managers and employees) so that modern technologies and innovation practices (related to Industry 4.0) can be successfully integrated into Bulgarian enterprises. Detailed step-by-step guidance will be developed, and the Upskilling lab 4.0 model will be introduced to national organizations and businesses interested in digital transformation. In 2018 BIA and Friedrich Ebert Stiftung Bulgaria participated in the project “Industry 4.0- Challenges and impact on the economic and social development of Bulgaria”. A list of proposals concerning Industry 4.0 was presented to the Ministry of the economy.

The National Competency Assessment System “MyCompetence” has been created as part of a project carried out by the Bulgarian Industrial Association (BIA). The “MyCompetence” System is an online platform in the field of human resource management and development. It offers competency profiles and job descriptions for key positions, lists of competencies, assessment tools, e-learning resources and other services for the assessment and development of workforce competencies.

- Bulgarian Industrial Capital Association (BICA)

In July 2021 the Sofia University started the implementation of the project “MODERN-A: MODERNIZATION in partnership through the digitalization of the academic ecosystem”. It is implemented in partnership with eight other universities in Bulgaria, three national employers’ organizations (BIA, BCCI, BICA) and over 20 associate partners from abroad. One of the main project goals is the implementation of programs with digital content, promoting distant learning and the development of electronic and cloud technologies within the learning process. The project activities envisage teacher training, specializations in foreign universities, scientists and students mobility. Student clubs for the development of entrepreneurial skills, presentation skills and digital creativity will be established within Sofia University and two other partner universities.

In 2019 BICA and the United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO) renewed their 2016 cooperation agreement and extended its application. The signed Partnership Memorandum empowers both organizations to develop projects and policies increasing SMEs competitiveness both to tackle key global challenges such as digitalization and cybersecurity and to balance knowledge and skills of the future workforce.

- Confederation of Employers and Industrialists in Bulgaria (CEIB)

CEIB actively participate in national forums dedicated to the digital transformation of the economy. In 2017 CEIB organized together with major tech companies the first national cloud summit where strategic partnership arrangements were discussed. In 2021 CEIB presented its views during a high-level conference, “The Green deal and digital transformation- opportunities for the competitiveness of the Bulgarian economy”, organized by the Deputy Chair of the Renew Europe Political Group in the European Parliament. As part of the annual awards “Mr and Mrs Economy”, CEIB rewards individual contributions to the ICT development.

- Confederation of Independent Trade Unions in Bulgaria (CITUB)

CITUB has started in 2021 a project dedicated to the development of unified digital profiles where a detailed list of competencies and skills will be elaborated. The project encompasses 17 economic sectors and foresees employee training on digital competence development. The project will be implemented in partnership with BIA, BICA, BCCI and the Ministry of Labor and Social Policy.

- Confederation of Labour “Podkrepa” (CL “Podkrepa”)

The sector structures of CL “Podkrepa” actively analyze the digital penetration within the sectors and pay specific attention to the development of digital skills through collectively agreed initiatives.

- Union for Private Economic Enterprise (UPEE)

UPEE pays specific attention to the cyber security issue, and since June 2021, a UPPE representative has joined the European Cyber Security Organisation (ECSO). Seeking to communicate the business needs to the government representatives, at the beginning of 2021, UPEE, together with a leading Bulgarian university, organized an online event called “Talking about policy, digitalization and sustainability: youth questions”. During the event, discussions focused on the cyber security and education-business dimensions.

- In the “Education” sector

- In Bulgaria for 2020 and 2021, the social partners agreed with the Sectoral employment contract in the system of school and pre-school education additional payments for teachers who work in the conditions of the online learning process (work from a distance in real-time).

- Example in the field of pre-school and school education after the introduction of the state of emergency in Bulgaria due to the spread of the COVID-19 virus and the adoption of the Law on Pre-school and School Education changes in a number of normative acts were adopted, incl. and of the LC. With the provision of art. 20 of the Law on the Protection of Human Rights and Freedoms stipulates that by the end of the 2019-2020 academic year, students’ education, as well as support for personal development, shall be carried out as far as possible from a distance in an electronic environment using ICT tools. The training includes distance learning hours, self-preparation, ongoing feedback on learning outcomes and assessment.

4. References

[1] National Statistics Institute of Bulgaria and Eurostat have been used as sources throughout this chapter.

[2] 10-49 employed

[3] 50-249employed

[4] The employment rate of persons aged 15 years or more.

[5] http://erc-online.eu/european-social-dialogue/database-european-social-dialogue-texts/

[6] https://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/submitViewTableAction.do

[7] The Economic and social council of the Republic of Bulgaria is comprised of three groups – Group 1 Employers, Group 2 Workers and Group 3 – Various interests

[8] https://www.nipa.bg/%D1%81%D0%BF%D1%80%D0%B0%D0%B2%D0%BA%D0%B0-%D0%B7%D0%B0-%D0%B4%D0%B5%D0%B9%D1%81%D1%82%D0%B2%D0%B0%D1%89%D0%B8-%D0%BA%D1%82%D0%B4/?lang=EN

[9] https://www.nsi.bg/bg/content/18665/%D0%BF%D1%83%D0%B1%D0%BB%D0%B8%D0%BA%D0%B0%D1%86%D0%B8%D1%8F/%D1%81%D1%82%D1%80%D1%83%D0%BA%D1%82%D1%83%D1%80%D0%B0-%D0%BD%D0%B0-%D0%B7%D0%B0%D0%BF%D0%BB%D0%B0%D1%82%D0%B8%D1%82%D0%B5-2018

Δεκ 26, 2021 | Research

STAGE 1

1. Introduction

The world of work is experiencing the Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR), a term to describe the chancing world of technology, its impact on work and life and the facilitation of globalisation in trade and services. It was first used by Klaus M Schwab, the founder and executive director of the World Economic Forum (WEF), in an article to contribute to debates of this topic during the 2016 Annual Meeting in Davos. [1]

In his book, Mark Carney, the former Governor of the Bank of England, defines this era as resulting from the:

Applications of artificial intelligence are spreading due to advances in robotics, nanotechnology and quantum computing. Our economies are reorganising into distributed peer-to-peer connections across powerful networks – revolutionising how we consume, work and communicate. Enormous possibilities are being created by the confluence of advances in genetic engineering, artificial intelligence, nanotechnology, materials science, energy storage and quantum computing. [2]

Carney suggests that 4IR will run from 2018 to, possibly, 2030 or beyond. [3] He points to how these ideas are in line with previous analysis of the impact of technology on work through the various industrial revolutions, including those of Adam Smith, Karl Marx, JM Keynes. Numerous Nobel Laureates, such as Joseph Stiglitz, [4] Paul Kruger, [5] and Amartya Sen [6] have also focused on the impact of technologies on employment, the growth of globalisation and the inter-connection of global economies.

The Fourth Industrial Revolution can summed up as the continuum from steam power, electrical power, through electronics and information technology to digitalisation, robotics, communications technology and artificial intelligence.

2. Ireland and the Fourth Industrial Revolution

Ireland was an early participant in the Fourth Industrial Revolution. It was an early location for computer manufacturing, providing high level employment in an emerging sector. The manufacture and assembly of hardware equipment led to the emergence of indigenous software enterprises and a key business sector which has become a world leader in software design. In more recent years the major social media companies have selected Ireland as their headquarters for the European, Middle East and Africa (EMEA).

Most of the major tech companies in the world, such as Apple, Microsoft, Dell, Intel, IBM, SAP, Facebook, LinkedIn, Twitter, HubSpot, eBay and PayPal are all located in Ireland. It is estimated by the Industrial Development Authority (IDA) that there are almost 1,000 tech companies in Ireland ranging from the global superpowers to embryonic start-ups. The sector contributed an estimated €44 billion to the Irish economy in 2020. Incomes in the sector are approximately 50% higher than in the rest of the economy, with some 105,000 employees, [7] while it is estimated that the percentage of the Irish population using the internet on a daily basis in January, 2021 was 91%. [8]

The IDA was set up by the Government in 1949 to attract Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) into the economy. It was established in 1969 as a non-commercial semi-State enterprise and this status was under-pinned by the Industrial Development Acts, 1986-2019. The IDA continues to be the major agency attracting multi-national companies to establish offices and subsidiaries in Ireland. [9] The Authority made a conscious decision in the 1960s to target newly emerging technology companies, in particular US based companies. However, some of these companies were already showing interest in Ireland as a country for investment, with IBM becoming the first US technology company to set up in Ireland, when it opened its Dublin sales office in 1956.[10] Since then there has been a steady flow of FDI by technology enterprises. Some key examples of these include:

Manufacturing